the art of love

[This post is unsuitable for people under 18.]

Analysing sexual positions and publishing sex manuals is something we often associate with the Sexual Revolution of the second half of the 20th century. But today I will not write about contemporary publications on the subject but rather go back to the times of Renaissance. Have you heard about “I Modi” (“The Ways”)? It also goes by the title “The Sixteen Pleasures”.

At the beginning of the sixteen century the idea of the sex manuals was associated with the classical traditions. Especially interesting seemed to have been the works of a lady called Elephantis – those works did not survive, but were cited in the ancient roman sources. Elephantis herself is said to have been Greek poet and physician, living in the 1st century BC. Apparently among her works there used to be sex manuals describing various sexual positions. Speaking about the sexual content of classical culture: we still have the Pompeii frescoes, about which I have written earlier (post available HERE). And the thing I want to write today about also started with the frescoes. In the first half of the 16th century Giulio Romano designed and decorated Federico II Gonzaga’s new Palazzo del Te in Mantua. Some of the frescoes there are indeed highly erotic!

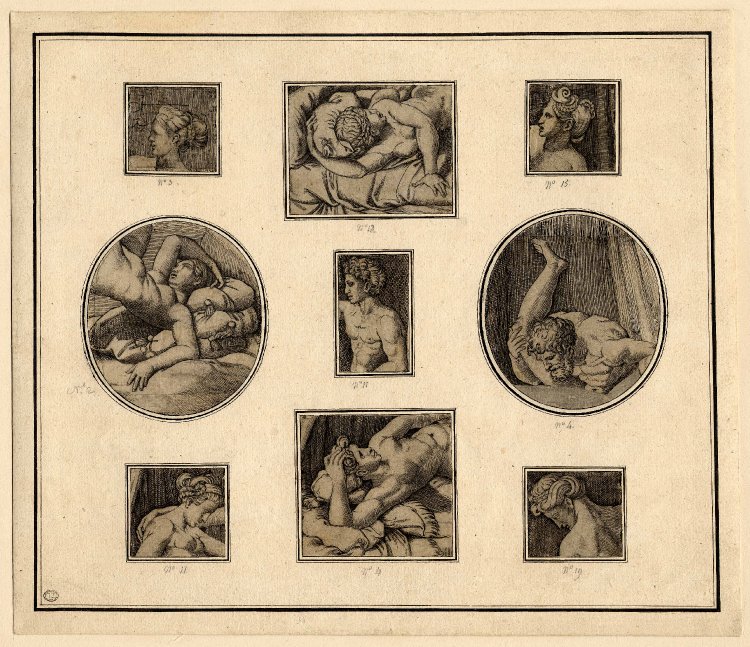

Giulio Romano’s drawings were most likely the source of inspiration for the first edition of “I Modi”: that was a set of prints by Marcantonio Raimondi, depicting various sexual positions. It was in 1524 – but that first edition was entirely destroyed and Marcantonio Raimondi was imprisoned by the Pope Clement VII! The publication was considered pernicious because it was widely available. The frescoes in the palace were rather private, so not that harmful, while printed matter may have circulated around the whole society! Consequently, the second edition of 1527 was also destroyed. There are some fragments in the British Museum that have traditionally been regarded as the only surviving pieces of Marcantonio’s originals. However, they may as well come from a single ‘replacement’ set, re-engraved in the same direction.

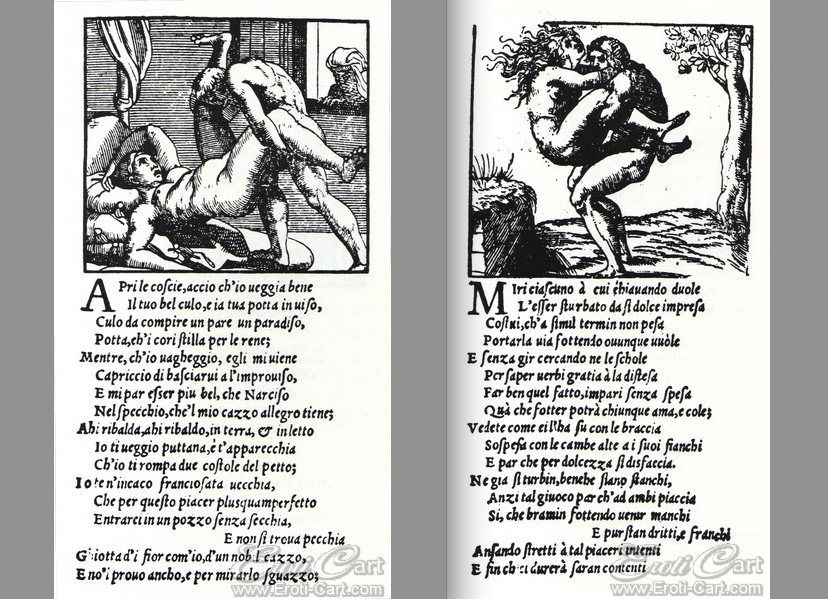

Interestingly, the second edition of “I Modi” was not only the set of images, but also contained descriptions in form of erotic poems written by Pietro Aretino. There is one woodblock copy of it, dating back to 1550 (in private collection).

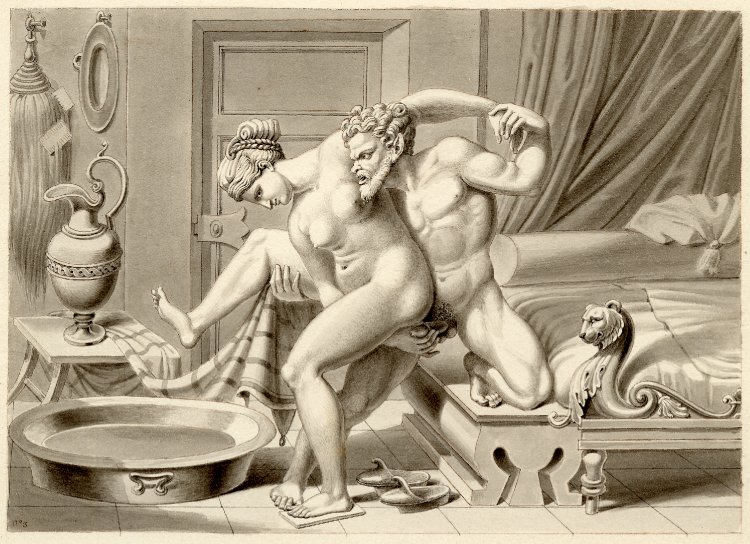

The lost Marcantonio’s prints were most likely the source of inspiration for Jean Frédéric Maximilien de Waldeck, who created a set of drawings in the mid-19th century (today in the British Museum). That version contains much more details than the 16th century woodblock copy. Some of the positions are quite acrobatic! Interestingly, there are 20 drawings, so the set contains 4 positions more than the original.

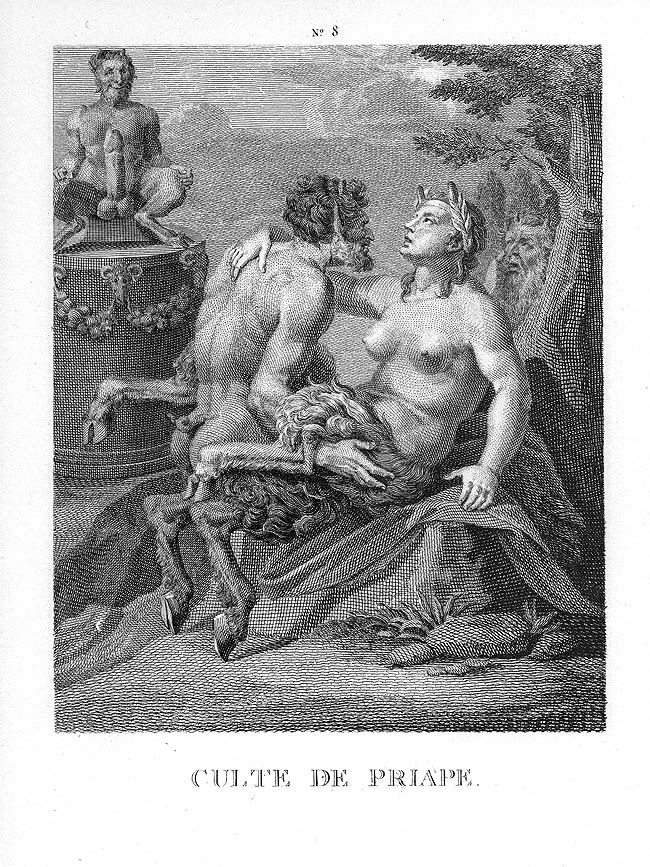

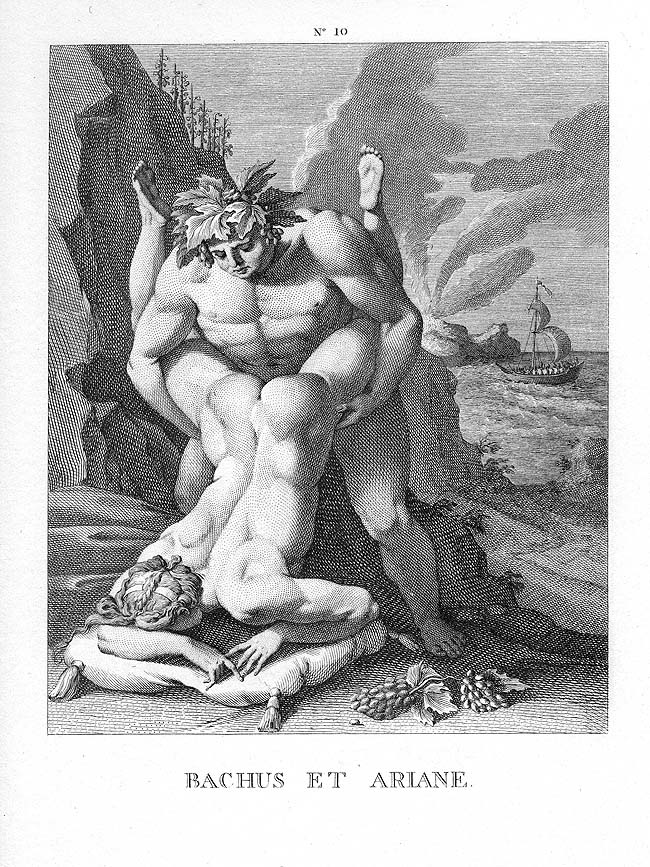

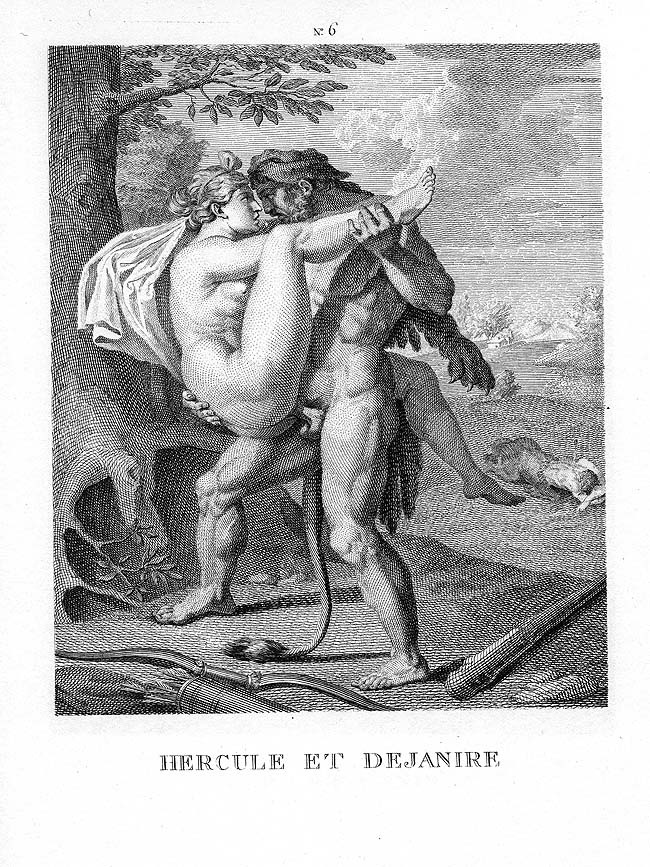

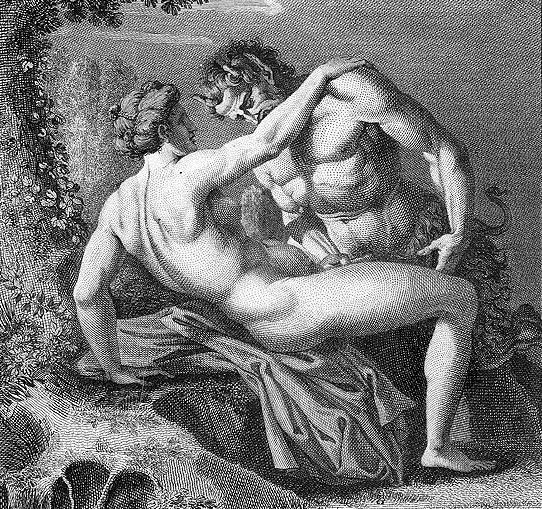

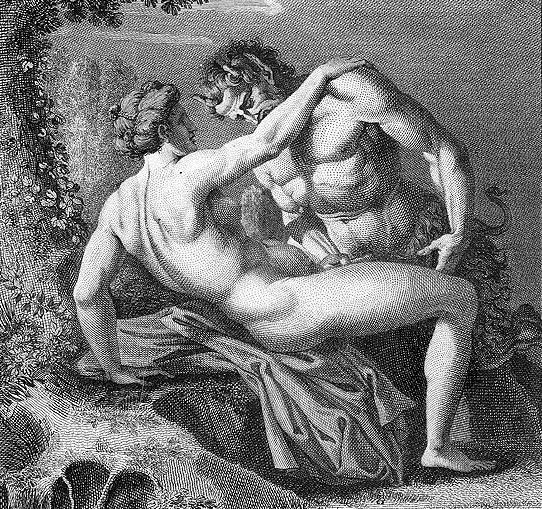

Undoubtedly the most famous set of prints associated with “I Modi” is the one made by Jacques Joseph Coiny at the end of the 18th century. It is described as after Agostino Carracci with sonnets by Aretino, but in fact that may have been a different project, although close to “I Modi”. In this case the compositions of the prints are not following the ones we know from woodcuts and drawings mentioned above. All the participants were here described here as ancient gods or classical figures. We also get the satyrs (male and female!): the mythological creatures famous for their lust.

The classical “cloak” was a often used in European art to justify the erotic content and to make the work of art more respectable. In this case, however, it does not work: even for a 21st century viewers those images may seem too graphic.

By the way, have you noticed the precision in depicting human muscles in those prints? Well, in case of females it may seem not very pretty. But even without considering the issue of aesthetic canons of the 16th century, we should admit that those positions require some strength, and on both sides! But (after seeing those prints) don’t you think now that there are some nicer ways to fulfill your New Year’s resolutions than working out alone in the gym?