Virgin Mary beats the devil!

There are legends that just live in European culture for centuries, since ancien Times till nowadays. There are motifs that keep coming back. One of those motifs – especially in Christian culture – is a story about a man who sold his soul to the devil. Source of inspiration for those stories was probably the legend of Theophilus of Adana.

The legend was created in the 6th century – allegedly written (in Greek) by Theophilus’ disciple, Eutychianus, not long after Theophilus’ death in 538. Theophilus was not a villain in this story: he administrated church treasury for the bishop of Adana in Cilicia, and was famous for his generosity and gentle heart, as well as empathy towards the poor and needy. When the bishop died, people wanted Theophilus to become new bishop, but he refused – he preferred to keep his former position. Unfortunately he lost it after the new bishop fired him due to some vicious (and untrue) gossips. Theophilus was very upset, and as a result he consulted certain Jew about how to regain his position. The Jew introduced Theophilus to the devil.

Theophilus regained his position and social respect after he signed contract with the devil – our hero sold his soul, and renounced Christ and Virgin Mary. But Theophilus was not a bad man, and soon his conscience started to bother him. He regretted his decision; decided to confess his sin to the bishop, and asked Virgin Mary for help. Mother of God managed to take back the document from the devil, and returned it to Theophilus when he was asleep. After Theophilus woke up, he burned the pact; died three days later, and his soul was redeemed.

The legend about Theophilus of Adana was very popular in medieval Europe; it was referred to in many sermons and prayers, and illustrated in artworks.

Especially interesting is a motif of Mother of God taking the document from the devil by using physical force – we will not find it in illustrations from the 11th or 12th centuries, but it was common in subsequent centuries. It was probably related to the popularity of “Miracles de Nostre Dame” by Gautier de Coinci (1177-1236): a group of fantastic stories featuring Virgin Mary saving sinners from various troubles. Many of those tales also appeared in “Cantigas de Santa Maria” (in medieval Galician), composed at the Court of King Alfonso X of Castile in the second half of the 13th century. For example, there is a story about a monk who sneaked into convent’s cellar and drank too much wine. Being drunk, the monk was attacked by the devil in various forms (a bull, a black man and a lion), but every time he was saved by Virgin Mary, who beat the devil.

Drunk monk and a lion (devil) beaten by Virgin Mary; Gautier de Coinci, Miracles de Nostre Dame, dekor. Jean Pucelle, 1328-1332, Bibliothèque nationale de France, NAF 24541, gallica.bnf.fr

I told you before about another story from that book, featuring agressive Mother of God, in a post entitled “Our Lady of the Baton” (available HERE).

And among those stories, illustrations of Theophilus’ legend developed; so we may see Virgin Mary piercing the devil with a cross…

Les miracles de la Vierge, mis en vers par Gautier de Coincy; Bibliothèque municipale de Besançon, Ms 551

… or beating him with a club…

… or using a whip on him (interestingly, the devil probably tried to swallow the document, as we can see him throwing it up):

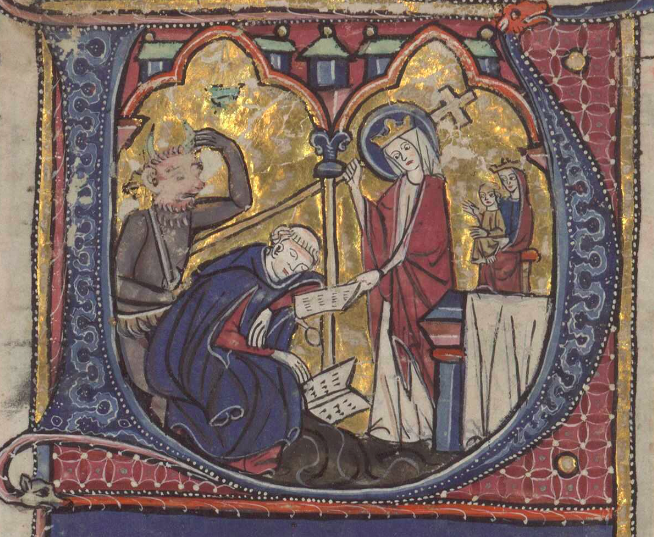

In a theatre play dating back to the second half of the 13th century – „Le Miracle de Théophile” by Rutebeuf (1245-1285) – we may find a dialogue in which Mother of God threatens the devil to punch him in the guts. Quite literally Mary punches the devil in earlier artwork: De Brailes Book of Hours, ca. 1240, British Library, Add MS 49999:

In past two decades various publications (often available online) have been published on the subject of Theophilus’ Legend. For example: a book by Jerry Root „The Theophilus Legend in Medieval Text and Image” (2017), as well as thesis on certain artworks (e.g. „Asserting Authority: The Canons’ Use of the Theophilus Legend and Marian Imagery at Notre-Dame in Paris” by Meagan Katherine Decker, 2013) or certain aspects of the legend (e.g. “Power and Prejudice: an Examination of Power Relations Expressed in Anti-Semitic Representations Across Time and Language in the Legend of Theophilus of Adana” by Robert Dean Gambles, 2019). None of them – just as an article written almost a century ago by Alfred C. Fryer („Theophilus, the Penitent, as Represented in Art”, 1935) – mention Central European late gothic examples. Meanwhile, it seems that the legend of Theophilus was known also here in Central Europe – perhaps it was not very popular, but apparently appeared in altarpieces dedicated to Virgin Mary.

One of the surviving examples in now in the National Museum of Finland in Helsinki: it is a pentaptych (retable with two pairs of movable wings) of an unknown original location, dating back to the 1420s. Its painted wings were created by otherwise well known German painter, Master Francke. Sculpted middle part of the retable contains some popular scenes of the cycle of Virgin: Nativity, Death and Assumption of Mary, her funeral, and Circumcision of Christ. In the right wing on the bottom we may see Theophilus praying to Madonna, with the devil standing behind, holding a contract.

Photo after: Kersti Markus, “The Saint Barbara Altarpiece of Master Francke and its Birgittine Context” (2014) (https://www.academia.edu/es/70370045/The_Saint_Barbara_Altarpiece_of_Master_Francke_and_its_Birgittine_Context)

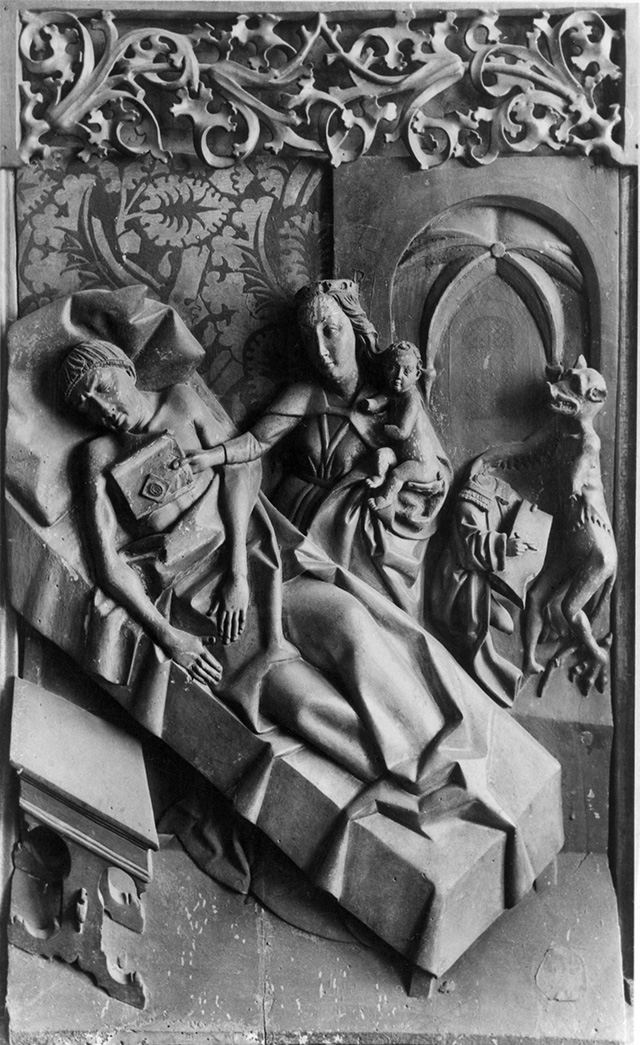

Meanwhile, in Cracow we have – or rather we used to have – a scene of the Legend of Theophilus among sculpted panels in polyptych of Lusina (I wrote about it HERE). It was also a pentaptych with partly painted wings and sculpted inner part, dedicated to Virgin Mary.

Apart from quite unique depiction of the Holy Family, there were images of Annunciation, Nativity and Death of the Virgin – all created in a workshop influenced by Veit Stoss, dating back to ca. 1505-1510. There also used to be an image depicting Virgin giving back the document to sleeping Theophilus (with a scene of signing the contract in the background), but it was looted, and most likely taken to Germany in the 1940s. The panel remains a war loss.

I very much hope that one day the lost pieces of retable of Lusina will be recovered; I also hope that the western scholars will in future refer to this exquisite artwork in their publications.