Medieval… jewelry?

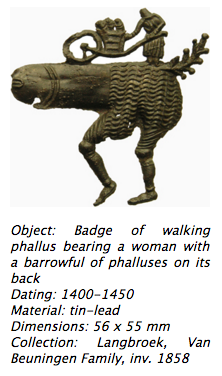

My previous post (available HERE, unsuitable for underage readers) was about an erotic book dating back to the 17th century. Its frontispiece has been decorated with a print depicting vendor of phalluses. Naturally, as I like to say, everything already happened in the Middle Ages! Also this Early-Modern print has its medieval sources of inspiration: depictions of a vendor (or a collector) of phalluses date back to much earlier than 17th century. For example, there are medieval badges depicting someone pushing a wheelbarrow full of phalluses.

The issue of obscene badges depicting sexual body parts (often anthropomorphized) is a difficult subject, as there are quite many of them, but it is not exactly known why people produced them. Scholars propose various interpretations, and we have to remember that even completely different ones do not necessary have to exclude each other. Firstly, those badges may have been rooted in the ancient beliefs that images referring to fertility have apotropaic powers (deterring evil). In such case, those badges (e.g. the ones depicting winged phalluses) may have been worn as amulets, perhaps even under clothes, hidden from view.

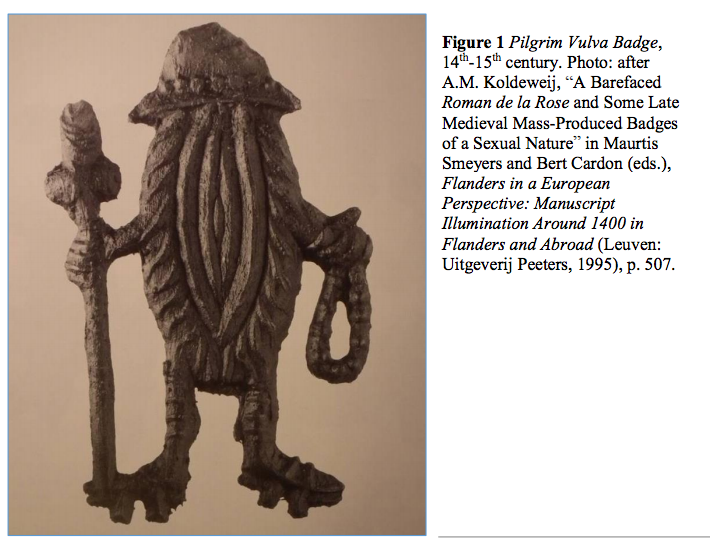

On the other hand, it is assumed that those may have been pilgrim badges, as it was popular in the Middle Ages to mark pilgrim status by wearing particular symbols or accessories. Some scholars think that pilgrim badges of sexual subject may have relate to the purpose of pilgrimage, such as prayer for fertility or sexual prowess. Also, it may be noted that the most common medieval symbol of pilgrimage – a shell (fr. coquille) – in French also had a meaning of female sexual organs. On the other hand, a 13th-century allegorical poem about love, entitled “Roman de la Rose”, contains description of an intercourse using a metaphor of a pilgrim approaching sanctuary (I wrote about that earlier, post is available HERE). So we should not be surprised that there are also medieval badges depicting vulvas dressed as pilgrims! Holding a very characteristic staff.

Naturally, it may have just be a bawdy visual joke. Even – or perhaps especially? – mocking religion. A beautiful example of that case is a badge depicting phalluses carrying a crowned vulva, as if it was a sacred image in venerated the liturgical procession.

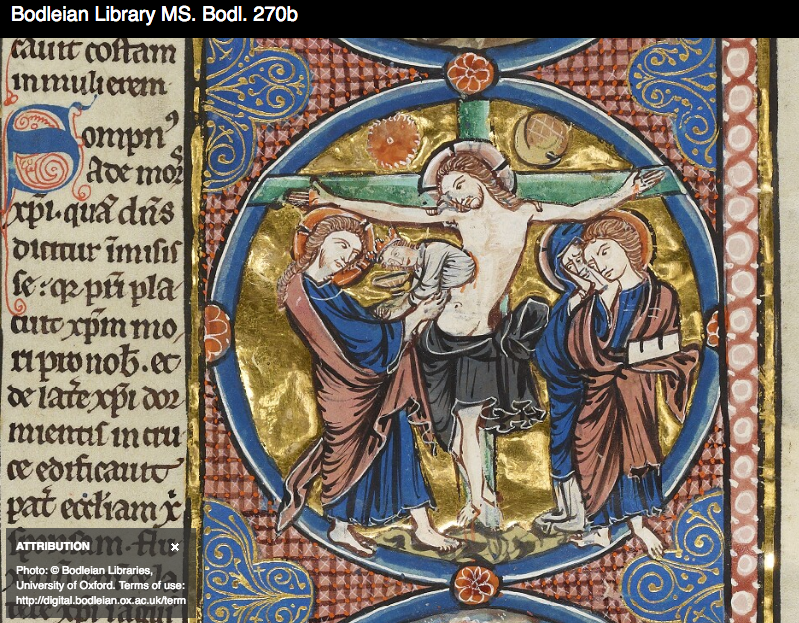

And here we must consider another aspect, and rather a risky one: that is the issue of “vulva-shaped” elements in religious art. We can not ignore the resemblance between vulva and mandorla (almond-shaped haloes), or, even more precisely – between vulva and Christ’s side wound, depicted separately for example in some medieval prayer-books.

You may say that this is a contemporary over-interpretation, but our medieval ancestors had the same visual associations as we do. The side wound of Christ, made by a spear, should rather be horizontal, not vertical; depicting it separately (out of the context of Christ’s body) makes it even more ambiguous. At the same time, medieval iconographical tradition proves that the side wound of Christ can actually be interpreted as a symbolic vagina. Not in a sexual meaning, but as a body part is involved in giving birth. A proof of that are miniatures in so called Bibles Moralisées, depicting birth of the Church (Ecclesia), which is being pulled out of Christ’s side wound!

I wonder if any theological aspects (or associations with a spear piercing Christ’s side) occurred to the medieval pilgrims who purchased those badges?

***

If you are interested in further details on interpretation of medieval body-part badges, I recommend you an article which was a source of most illustrations from this post: Ben Reiss, “Pious Phalluses and Holy Vulvas: The religious Importance of Some Sexual Body-Part Badges in Late-Medieval Europe (1200-1550)”, in: “Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture”, Volume 6, Issue 1, 2017, pp. 151-176: https://digital.kenyon.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1291&context=perejournal

Also, there are some further terrific examples in a post on OTULINA blog.