Late-gothic masterpiece from Vienna

A myth of a glorious imperial past is still vivid among many inhabitants of former Austro-Hungarian Empire and I must admit I am one of them. I very much value the fact that now and then I have a chance to participate in a party where – at certain point of the evening – everyone (in spite of speaking different languages) stands up and drinks the health of His Majesty Emperor Franz Joseph Habsburg. That is why when I say: “I visited the capital city” I mean Vienna, not Warsaw.

Obviously, Vienna is full of beautiful sights, magnificent monuments and museums. However, not all of them are widely popular among tourists; I have a feeling that not many people visit Schottenstift Museum, placed in the “Scottish” Benedictine Abbey (Benediktinerabtei unserer Lieben Frau zu den Schotten). The Abbey was funded in 1155 by Henry II Jasomirgott of Austria exclusively for the Irish-Scottish Benedictine monks, transferred from the Abbey of St James in Regensburg (also called Schottenstift). In 1418 the Scottish Abbey in Vienna was transformed into a regular Benedictine Abbey (for German-speaking monks) but its name Schottenstift was retained.

The museum itself is a small one, and at first glance the exposition consists mainly of low-class Early-Modern paintings. But there is a true treasure in one of the rooms here: panels from the wings of 15th century altarpiece, created by so called Master of Schotten Altar (Schottenmeister).

The fifteenth-century retable was created after the church’s choir (most likely along with former main altar), was damaged in the first half of the 15th century in an earthquake. The late-gothic altar was replaced in the seventeenth century and unfortunately it did not survive; only 21 panels remained of original 24 decorating the altar-wings. Those painted panels were visible in the middle-opening of the altar (containing scenes from the Life of Virgin) and when the retable was completely closed (showing a Passion cycle).

For a scholar specialising in late-gothic panel painting in Central Europe the Viennese Schotten Altar is one of the most important artworks. Workshop of its creator was widely influential for the 15th-century art throughout Central and Eastern Europe, where it introduced elements of Early-Netherlandish painting, following such masters as Jan van Eyck or Rogier van der Weyden. Those elements are, for instance: expressive depictions of individual faces, carefully painted everyday objects, landscapes full of interesting details, as well as dynamic and moved angular folds of clothes. One of the panels (Entry to Jerusalem) contains the date 1469, but for a long time many scholars assumed that it would be too early for the central-European artist to create such a “netherlandish” piece at that time, so the retable used to be dated to between 1469 and ca. 1480. However, it is well known that a date in the artwork is usually that of completion, so we now should stop thinking that Central Europe always needed a lot of time to catch up with the latest trends of Western Europe! This Viennese altarpiece, highly influenced by the art of Rogier van der Weyden, was created in the late 1460s, almost contemporary to the Netherlandish master it followed (van der Weyden died in 1464).

In the past it was also assumed that two masters had created Schotten Altarpiece: the Elder and the Younger, but this hypothesis is no longer accepted. Obviously, such a big commission must have been completed by a group of painters, but they all worked in one workshop, led by one main Master. Recently, prof. Robert Suckale proposed that this main master may be identified as Hans Siebenbürger, Transilvanian painter active in Vienna, who died in 1483. It is worth noticing that at the time when the Schotten Altar was created, the Abbot of Schotten Abbey was Matthias Vinckh (Fink), who also came from Transylvania.

In any case, the Schotten Altar is a true masterpiece of Viennese fifteenth century painting. It was undoubtedly created by a local master, as the Biblical scenes have been settled in the Viennese cityscape! There are characteristic buildings in the background of several images, and the Flight to Egypt is placed against carefully depicted view of Vienna.

Details are most interesting aspects of these panels: I love the everyday objects depicted here, such as pots and glasses, furniture or fabrics, which recreate the everyday life in the Central Europe in 15th century. Only the panel of Birth of the Virgin contains so many of such details!

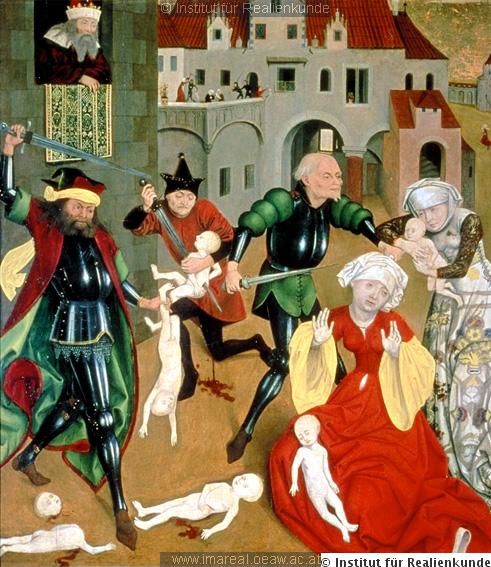

And also, look at the clothes: Saint Elisabeth is wearing fashionable narrow sleeves with lots of buttons, while two mourning mothers in the Massacre of Innocents are dressed in maternal dresses with characteristic laces.

One of the women has her dress unlaced on her womb, while the other has her laces tied up tightly on her side. I suspect that this way the artist wanted to depict information given in the Gospels, that Herod “gave orders to kill all the boys in Bethlehem and its vicinity who were two years old and under” (Mt 2:16): so he pictured one of the women as a mother of a newborn (so she has not yet regain her silhouette from before she was pregnant) while the other apparently gave birth some time ago and now she may tie her laces up again.

There is a theory that painters tend to give their characters their own features or features close to those of members of their own family. That may be related to the habit of practicing painting by portraying members of family or by creating self-portraits, using mirror. If that is true, we could assume that the Master of Schotten Altar had sunken cheeks and heavy thick eyelids. In the Schotten Altar we may find a lot of different, individual faces, but all the men there seem to be tired (or suffer from hangover).

And finally I’d like to take my chance to complain about my own, personal frustration: about how the Western world does not care about Central European art. The thing is that many museums, creating their catalogues, use a widely respected database Union List of Artist Names® created by the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles. I was very much surprised when I discovered that not only that database sustains previous (and currently rejected) division into two Schotten Masters, but – most of all – it gives the dating of their activity to late 14th-early 15th century! Would it be possible that the Getty experts used some unreliable sources for their database, such as – let’s say – Wikipedia? Because English article in Wikipedia contains some similar nonsense:

The image is good, but the description… refers to a different altarpiece! As it happens, there is a late-fourteenth retable in Schotten in Hessen (Germany) and apparently an English-speaking author of this article not only confused Austria with Germany, but most of all he did not get the subtle difference between Schottenaltar (Schotten Altar) and Schotteneraltar (Altar from Schotten).

In 2015 I have exchanged some emails with the Getty Institute, trying to convince them to change the dating of the Schotten Master in their database. I have explained that there are two different altars: Vienese Schotten Altar, dating back to 1469 and retable in Schotten, dating back to ca. 1390. I have given a lot of references – although they were all in German. Apparently, it was not convincing for the Getty experts, as today (screen of 12 January 2019) the entry http://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabularies/ulan/ looks like this:

Shall I give up now and just pour myself some Austrian wine to drink the health of His Majesty Franz Joseph?